Pain vs. Soreness

What is the difference between pain and soreness?

By knowing the difference between an acceptable level of pain or soreness and when you should suspect a possible injury helps you to best manage your symptoms.

Firstly, pain itself is very complex. It is a very personal experience and varies from person to person.

In general, pain can be defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage”. Pain is created as an output of the nervous system (brain, spinal cord) in response to a perceived threat from bodily tissues and the environment. It is not always (but can be) an actual threat.

Pain doesn’t equal tissue damage. Structures can be sensitive and painful while sustaining no real damage — a structure can be sensitive in specific positions, loadings, and movement patterns while remaining unharmed.

This means that not everyone who experiences pain or soreness needs to stop doing activities or exercises that are painful or sore, although for some, this may be advisable.

For some, advice, reassurance, and guidance around their symptoms and offering strategies on how they can modify or reduce their activity may be enough to reduce their pain. For others, a period of active rest, which may include avoiding or stopping painful, aggravating tasks, is advisable.

What is ‘good’ or acceptable pain?

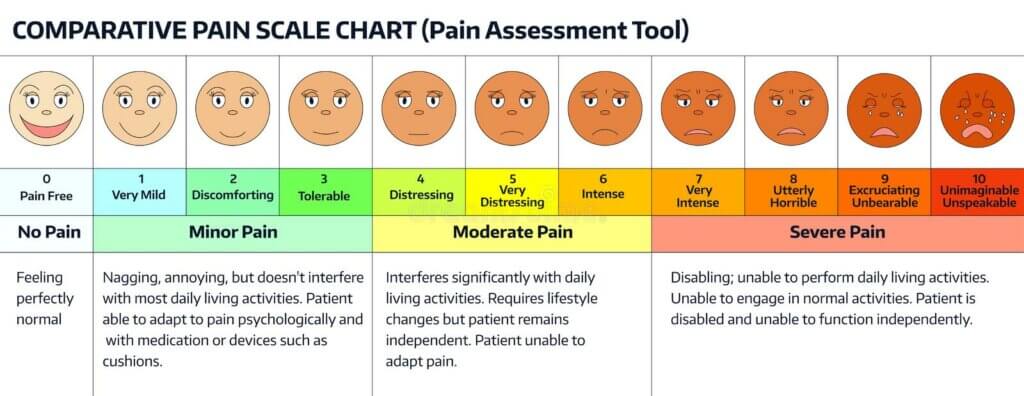

Acceptable pain can be specific to each individual. Although, as a general rule, it can be classified as a rating of 0–3/10 on the visual analogue scale of pain. This can range from an awareness of a certain area of your body, mild discomfort or pain that does not interfere with your activities, and pain that is slightly distracting but tolerable.

Acceptable pain may be a lower level of discomfort you experience as you’re rehabbing an injury, or it may be a level of discomfort that your physiotherapist is happy for you to work through when completing your home or gym-based rehab exercises. One classification of good pain is the delayed onset of muscle soreness.

What are DOMs?

Exercise-related muscle soreness can occur when we place muscles under stress.

This is called “delayed onset of muscle soreness,” or DOMs, as it is more commonly known as.

This soreness is a result of small, unharmful “tears” on these unused muscle fibers. As the body repairs these small tears, the muscles become stronger. Short-term muscle soreness is a healthy and expected result of exercise. Normal muscle soreness and fatigue can last between 24 and 72 hours after a muscle-stressing activity. Muscle soreness may feel achey, stiff, or tight.

The amount of soreness you have will depend on the time and intensity of your exercise. It can also depend on whether the activity was new to you and how intense your workout was.

What can you do when you are experiencing muscle soreness?

Give your muscles adequate time to recover before working them again. Generally, 24–72 hours will allow enough time for the muscles to recover and be ready to train again.

During this time, aim to stay active. Light, tolerable movement can assist your recovery. Complete rest is generally not advisable.

Adding variety to your exercises can allow for certain muscle groups to be worked and then have time to recover while other muscle groups can be worked in the meantime. For example, working your upper body and then, while those muscles are recovering, working your lower body.

How to prevent DOMs?

Performing an active warm-up prior to a gym, running session, or sporting match can help to prepare your muscles for loading-based activity.

Prior to, during, and following exercise, it is important to ensure you are adequately hydrated. Following loading activity, especially resistance training, consuming protein can help with muscle repair.

Lastly, limiting drastic increases in the volume or intensity of your workouts will help reduce DOMs. Aim to gradually progress your workouts and give yourself adequate rest between workouts.

What is ‘bad’ pain?

Bad pain may be if your symptoms are persistent, worsening, classified as a high pain rating (6-10/10 pain scale rating), keeping you awake at night, or made worse with continued activity. Bad pain may indicate an injury.

You may experience sharper, shooting symptoms that do not resolve within 24-72 2 hours. Symptoms may be brought on by a specific movement or incident. You may have pins and needles, tingling, numbness, or experience burning sensations. Your pain may be more constant throughout the day and experienced when at rest or performing tasks.

When to seek help?

If you are experiencing symptoms that are not improving over time or worsening with the continuation of your normal daily activities, then it may be beneficial to seek advice from a physiotherapist.

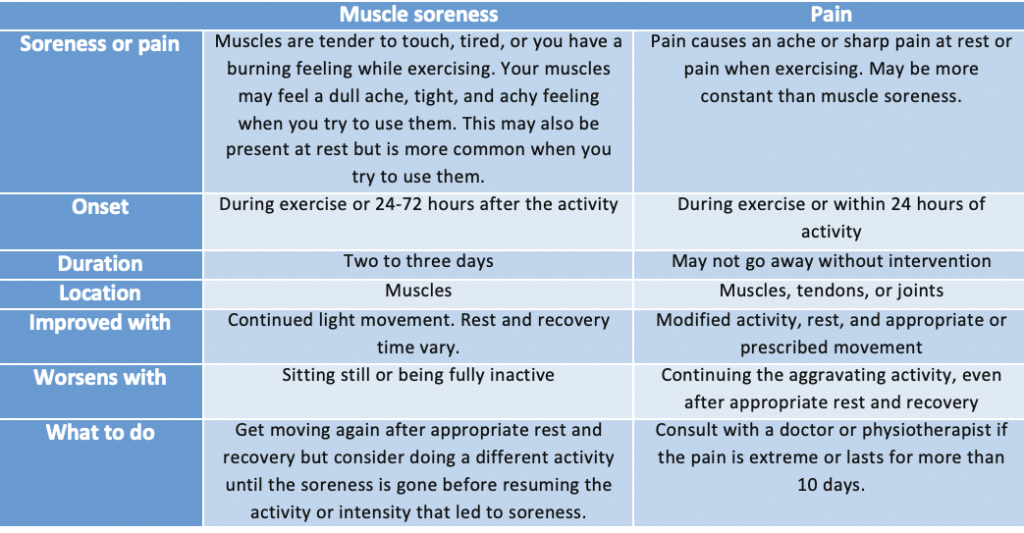

Below outlines some of the key differences between pain and muscle soreness: